Historical connections

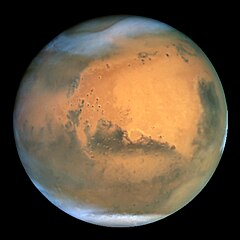

Mars is named after the Roman god of war. In Babylonian astronomy, the planet was named after Nergal, their deity of fire, war, and destruction, most likely due to the planet's reddish appearance.[112] When the Greeks equated Nergal with their god of war, Ares, they named the planet Ἄρεως ἀστἡρ (Areos aster), or "star of Ares". Then, following the identification of Ares and Mars, it was translated into Latin as stella Martis, or "star of Mars", or simply Mars. The Greeks also called the planet Πυρόεις Pyroeis meaning "fiery". In Hindu mythology, Mars is known as Mangala (मंगल). The planet is also called Angaraka in Sanskrit, after the celibate god of war, who possesses the signs of Aries and Scorpio, and teaches the occult sciences. The planet was known by the Egyptians as "Ḥr Dšr";;;; or "Horus the Red". The Hebrews named it Ma'adim (מאדים) — "the one who blushes"; this is where one of the largest canyons on Mars, the Ma'adim Vallis, gets its name. It is known as al-Mirrikh in Arabic, and Merih in Turkish. In Urdu and Persian it is written as مریخ and known as "Merikh". The etymology of al-Mirrikh is unknown. Ancient Persians named it Bahram, the Zoroastrian god of faith and it is written as بهرام. Ancient Turks called it Sakit. The Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese cultures refer to the planet as 火星, or the fire star, a name based on the ancient Chinese mythological cycle of Five elements.

Its symbol, derived from the astrological symbol of Mars, is a circle with a small arrow pointing out from behind. It is a stylized representation of a shield and spear used by the Roman God Mars. Mars in Roman mythology was the God of War and patron of warriors. This symbol is also used in biology to describe the male sex, and in alchemy to symbolise the element iron which was considered to be dominated by Mars whose characteristic red colour is coincidentally due to iron oxide.[113] ♂ occupies Unicode position U+2642.

Intelligent "Martians"

The popular idea that Mars was populated by intelligent Martians exploded in the late 19th century. Schiaparelli's "canali" observations combined with Percival Lowell's books on the subject put forward the standard notion of a planet that was a drying, cooling, dying world with ancient civilizations constructing irrigation works.[114]

Many other observations and proclamations by notable personalities added to what has been termed "Mars Fever".[115] In 1899 while investigating atmospheric radio noise using his receivers in his Colorado Springs lab, inventor Nikola Tesla observed repetitive signals that he later surmised might have been radio communications coming from another planet, possibly Mars. In a 1901 interview Tesla said:

It was some time afterward when the thought flashed upon my mind that the disturbances I had observed might be due to an intelligent control. Although I could not decipher their meaning, it was impossible for me to think of them as having been entirely accidental. The feeling is constantly growing on me that I had been the first to hear the greeting of one planet to another.[116]

Tesla's theories gained support from Lord Kelvin who, while visiting the United States in 1902, was reported to have said that he thought Tesla had picked up Martian signals being sent to the United States.[117] However, Kelvin "emphatically" denied this report shortly before departing America: "What I really said was that the inhabitants of Mars, if there are any, were doubtless able to see New York, particularly the glare of the electricity."[118]

In a New York Times article in 1901, Edward Charles Pickering, director of the Harvard College Observatory, said that they had received a telegram from Lowell Observatory in Arizona that seemed to confirm that Mars was trying to communicate with the Earth.[119]

Early in December 1900, we received from Lowell Observatory in Arizona a telegram that a shaft of light had been seen to project from Mars (the Lowell observatory makes a specialty of Mars) lasting seventy minutes. I wired these facts to Europe and sent out neostyle copies through this country. The observer there is a careful, reliable man and there is no reason to doubt that the light existed. It was given as from a well-known geographical point on Mars. That was all. Now the story has gone the world over. In Europe it is stated that I have been in communication with Mars, and all sorts of exaggerations have spring up. Whatever the light was, we have no means of knowing. Whether it had intelligence or not, no one can say. It is absolutely inexplicable.[119]

Pickering later proposed creating a set of mirrors in Texas with the intention of signaling Martians.

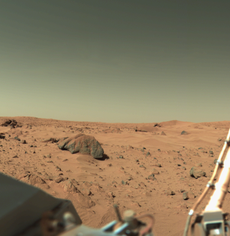

In recent decades, the high resolution mapping of the surface of Mars, culminating in Mars Global Surveyor, revealed no artifacts of habitation by 'intelligent' life, but pseudoscientific speculation about intelligent life on Mars continues from commentators such as Richard C. Hoagland. Reminiscent of the canali controversy, some speculations are based on small scale features perceived in the spacecraft images, such as 'pyramids' and the 'Face on Mars'. Planetary astronomer Carl Sagan wrote:

| “ | Mars has become a kind of mythic arena onto which we have projected our Earthly hopes and fears. | ” |

| —Carl Sagan, Cosmos[120] | ||

In fiction

The depiction of Mars in fiction has been stimulated by its dramatic red color and by early scientific speculations that its surface conditions not only might support life, but intelligent life.

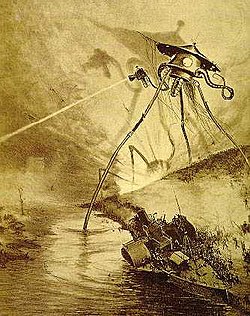

Thus originated a large number of science fiction scenarios, the best known of which is H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds, published in 1898, in which Martians seek to escape their dying planet by invading Earth. A subsequent radio version of The War of the Worlds on October 30, 1938 was presented as a live news broadcast, and many listeners mistook it for the truth.[121]

Also influential were Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles, in which human explorers accidentally destroy a Martian civilization, Edgar Rice Burroughs' Barsoom series and a number of Robert A. Heinlein stories before the mid-sixties.

A comic figure of an intelligent Martian, Marvin the Martian, appeared on television in 1948 as a character in the Looney Tunes animated cartoons of Warner Brothers, and has continued as part of popular culture to the present.

Author Jonathan Swift made reference to the moons of Mars, about 150 years before their actual discovery by Asaph Hall, detailing reasonably accurate descriptions of their orbits, in the 19th chapter of his novel Gulliver's Travels.[122]

After the Mariner and Viking spacecraft had returned pictures of Mars as it really is, an apparently lifeless and canal-less world, these ideas about Mars had to be abandoned and a vogue for accurate, realist depictions of human colonies on Mars developed, the best known of which may be Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars trilogy. However, pseudo-scientific speculations about the Face on Mars and other enigmatic landmarks spotted by space probes have meant that ancient civilizations continue to be a popular theme in science fiction, especially in film.[123]

Another popular theme, particularly among American writers, is the Martian colony that fights for independence from Earth. This is a major plot element in the novels of Greg Bear and Kim Stanley Robinson, as well as the movie Total Recall (based on a short story by Philip K. Dick) and the television series Babylon 5. Many video games also use this element, including Red Faction and the Zone of the Enders series. Mars (and its moons) were also the setting for the popular Doom video game franchise and the later Martian Gothic.